- Show Menu

- Contact Us

- FAQs

- Reader Service

- Survey Data

- Survey Winners

- Testimonials

- Upcoming Events

- Webinars

- White Papers

ISMP’s Best Practices for Medication Safety

Q&A with Christina Michalek, BSc Pharm, RPh, FASHP, Medication Safety Specialist

Q&A with Christina Michalek, BSc Pharm, RPh, FASHP, Medication Safety SpecialistInstitute for Safe Medication Practices

Pharmacy Purchasing & Products: What are some of the most common errors reported to ISMP this year that have led to patient harm, and how should these errors be addressed?

Christina Michalek, BSc Pharm, RPh, FASHP: Each year, ISMP receives reports of errors involving high-alert medications, and this year was no exception. This is concerning, as high-alert medications carry a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when they are used in error, and the harm caused can be devastating.

The ISMP 2018-2019 Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices for Hospitals were developed to identify, inspire, and mobilize widespread, national adoption of best practices for specific medication safety issues that continue to cause fatal and harmful errors in patients, despite repeated warnings in ISMP publications.1 The intent of these best practices is to draw attention to proper management of these medications.

Three new recommendations were added in December 2017:

- Best Practice 12: Eliminate the prescribing of fentaNYL patches for opioid-naïve patients and/or patients with acute pain. The rationale behind Best Practice 12 is the prevalence of serious adverse drug events, including fatalities, involving fentaNYL transdermal patches. There is a knowledge deficit around proper use of this particular delivery system, especially in identifying appropriate patients. FentaNYL patches are only indicated for persistent, chronic pain that requires around-the-clock treatment, and they are only to be used in opioid-tolerant patients. ISMP has recognized that some practitioners do not understand the definition of opioid-tolerant or how to recognize an opioid-tolerant patient (see SIDEBAR 1). Systems must be established with triggers to guide appropriate use; for example, EHRs and medication orders should require documentation of the patient’s opioid status and type of pain (eg, chronic vs acute).

- Best Practice 13: Eliminate injectable promethazine from the hospital. The ISMP 2018-2019 Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices for Hospitals state that organizations should remove access to medications known to be harmful when other options are available. Eliminating promethazine from the hospital is a priority due to the potential harmful effects of this drug, which can cause necrosis and lead to amputation. Furthermore, other generic injectable antiemetics, such as ondansetron, are available to treat nausea and vomiting. Promethazine should be replaced using an automatic therapeutic substitution policy and eliminated as an option from all medication order screens, order sets, and protocols.

To read about one organization’s process to eliminate use of promethazine injection, see the presentation by Kelly Besco, PharmD, FISMP, CPPS, Medication Safety Officer, OhioHealth Pharmacy Services, at: www.eventscribe.com/uploads/eventScribe/PDFs/2018/2104/635197.pdf.

- Best Practice 14: Seek out and use information about medication safety risks and errors that have occurred in organizations outside of your facility and take action to prevent similar errors. The emphasis of this best practice is on being proactive, as ISMP has noted that the same medication errors occur repeatedly across multiple organizations. ISMP suggests that hospitals dedicate a leader to be responsible for all medication safety activities in the organization. Key components of this role include networking with other facilities, creating a plan to prevent medication errors, monitoring safety efforts, and sharing results.

In early 2018, ISMP introduced a Self Assessment for High-Alert Medications,2 which is designed to:

- Heighten awareness of distinguishing systems and practices related to the safe use of 11 categories of high-alert medications

- Assist the interdisciplinary team in proactively identifying opportunities for reducing patient harm when prescribing, storing, preparing, dispensing, and administering high-alert medications

- Create a baseline of the organization’s efforts to evaluate risk and evaluate those efforts over time

Many organizations have already taken advantage of this assessment, and the tool is still available for interested organizations. ISMP is now in the process of releasing some of this preliminary comparative data.

PP&P: Which ISMP Best Practices suffer from low adoption rates?

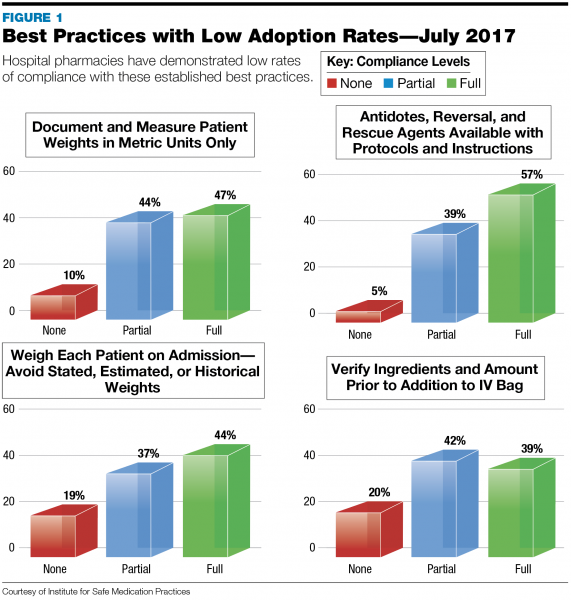

Click here to view a larger version of this Figure

Michalek: Due to low rates of compliance, ISMP is asking hospitals to focus on these existing best practices (see FIGURE 1):

- Best Practice 2b: Require a hard stop verification of an appropriate oncologic indication for all daily oral methotrexate orders. Because methotrexate is rarely given orally for this indication, clarify daily orders for oral methotrexate for non-oncology uses (when a hard stop cannot be provided). Hospitals should work with their software vendors and IT departments to ensure this hard stop is in place.

- Best Practice 2c: Provide specific patient and/or family education for all oral methotrexate discharge orders. Ensure that the process for providing discharge instructions for oral methotrexate includes clear written and verbal instructions that review the dosing schedule, emphasize the danger of taking extra doses, and specify that the medication should not be taken “as needed” for symptom control. Provide all patients receiving oral methotrexate with a copy of the ISMP high-alert medication leaflet on oral methotrexate (available at www.ismp.org/AHRQ/default.asp).

- Best Practice 3a: Obtain an actual patient weight. Weigh each patient upon admission and during each appropriate outpatient or emergency department encounter. Avoid the use of a stated, estimated, or historical weight.

- Best Practice 3b: Weigh and document patient weights in metric units only. Provide conversion charts from kilograms (or grams for pediatrics) to pounds near all scales, so that patients can be told their weight in pounds, if requested. However, computer information systems, medication device screens (eg, infusion pumps), and preprinted order forms should include prompts for the patient’s weight only in metric units.

- Best Practice 9: Ensure all appropriate antidotes, reversal agents, and rescue agents are readily available. Directions for use/administration should be readily available in all clinical areas where the antidotes, reversal agents, and rescue agents are used.

- Best Practice 11: When compounding sterile preparations, verify ingredients and amounts prior to addition to the final container. Eliminate the use of proxy methods of verification for compounded sterile preparations (eg, the syringe pull-back method). Use technology to assist in the verification process (eg, bar code scanning verification of ingredients, gravimetric verification, robotics, IV workflow software) to augment manual processes.

PP&P: What patient education and follow-up should occur to help prevent patient harm?

Michalek: It is not uncommon for organizations to bypass patient education. This is unfortunate, as the proper education of patients is critical to preventing medication errors. During the discharge medication reconciliation process, each prescription should be discussed with the patient. Describe the purpose of each medication and how it should be taken. Compile a targeted list of high-risk patients (ie, those on high-risk or multiple medications), who should receive follow-up phone calls to verify medication compliance and address any questions they may have. Because patients may be distracted or not able to fully comprehend instructions at discharge, follow-up phone calls are critical to ensure medications are taken as instructed. The pharmacist can make these calls, or the technician or nurse can screen for the need and then alert the pharmacist that a call is required.

In reviewing the most common medication errors that occurred within the past year, ISMP noted that a lack of proper discharge medication reconciliation and follow-up were a common thread in medication noncompliance and errors. A simple conversation can prevent significant patient harm. For example, during discharge medication reconciliation, if the pharmacist or technician refers to the patient’s diabetes medication, and the patient responds that they do not have diabetes, that conversation has prevented a medication error.

PP&P: What are some considerations for avoiding vaccine errors?

Michalek: More than 500 vaccine error events have been reported to ISMP this year. Many of these errors occur due to confusion among age-dependent vaccine formulations. In addition, vaccine name and abbreviation misinterpretations, as well as misunderstanding of the various vaccine components, may result in errors. The most common contributing factors to vaccine errors are listed in TABLE 1.

Several approaches can help prevent vaccine errors. For example, vaccine storage locations should be clearly marked. In addition, bar code medication administration (BCMA) should be established prior to use; an EHR order must be present prior to scanning and administration. The EHR order should be linked to a specific patient, to alleviate age-related vaccine mistakes. Finally, vaccines with two components should be stored together or repackaged and stored together upon arrival into the facility. For example, a powder and a diluent should be stored together, as should two liquid components. A simple rubber band around the two components, or placing the components together in a plastic bag, is effective. It may be useful for manufacturers to consider packaging all vaccine components together in one package to help reduce confusion.

PP&P: How can pharmacy help prevent medication errors due to a patient’s drug allergies?

Michalek: An ISMP work group is currently collaborating with the ECRI Institute on an initiative to improve allergy documentation in order to accurately characterize and distinguish adverse drug reactions, toxicities, intolerance, idiosyncrasies, and allergies.3 At this time, no specific recommendations have been made; it is anticipated that recommendations will be available by the end of the year.

PP&P: How can pharmacists help prevent look-alike/sound-alike (LA/SA) drug errors?

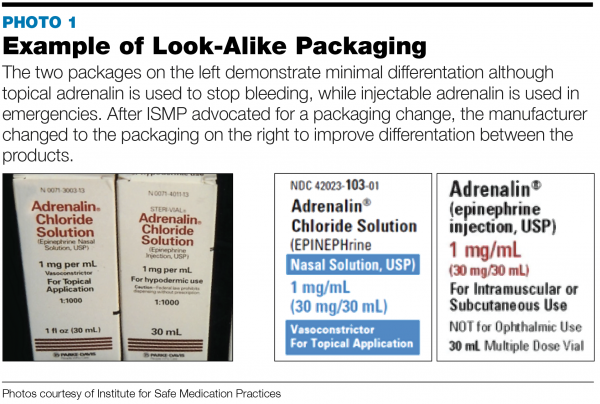

Michalek: Use of Tall Man lettering is critical to illustrate differentiation among products. A format for capital and lowercase letters, and examples of Tall Man lettering, are available on the ISMP website (www.ismp.org/recommendations/tall-man-letters-list). Combatting LA/SA packaging is more challenging; some manufacturers are committed to making significant strides to provide differentiation among similar medication packages, including drug names and doses, while other manufacturers are less motivated. Moving forward, manufacturers should commit to a robust strategy of differentiation to prevent possible errors.

Upon receiving an error report related to a LA/SA product, ISMP may contact the manufacturer and advocate for a packaging change. For example, we received a report that one company’s packaging for adrenalin and adrenalin chloride was highly similar (see PHOTO 1). Thereafter, the company changed the packaging to better differentiate between the nasal solution and the injection solution. If a problem with lack of product differentiation persists, it may be prudent to order from a different manufacturer. However, in an age of drug shortages, this too can be a challenge. Moreover, there is no guarantee that a new item will be sufficiently differentiated. Communication among organizations, manufacturers, and ISMP should continue to improve packaging differentiation, which can help reduce the possibility of error.

PP&P: What staff training must occur to improve medication safety?

Michalek: Preventing medication errors must be a multidisciplinary effort and should include staff training and targeted education. All staff handling medications should receive basic safety training, while those involved in the medication management process and those who are responsible for analysis of near-miss events and errors should receive more targeted training. Medication safety competencies should be assessed on an annual basis. For those staff members imbued in medication safety work—for example, the medication safety officer, members of the medication safety committee or P&T committee, and quality and risk professionals—more robust, targeted medication safety training is required. These staff members should learn how to identify and analyze errors from a systems perspective, so changes can be implemented to prevent ongoing problems resulting from a poor process. Rather than blaming an individual who made an error, focus on fixing the system that allowed that error to occur.

PP&P: What can an organization do to foster a culture of safety?

Michalek: First of all, measure the current state of your organization’s culture. Thereafter, address any barriers that have been identified one by one, focusing on the most critical first. One of the most significant challenges is ensuring staff feels comfortable reporting and discussing errors as well as near-misses; if errors are not reported, they cannot be remedied. Some organizations increase reporting by offering a “good catch” or similar award to practitioners who identify a safety issue. Providing follow-up and feedback to those who report errors and/or safety issues is a positive step toward creating a culture of safety. Evaluate your hospital’s safety culture every 1-2 years, and then be sure to utilize the data you have gleaned.

An effective organization values safety over efficiency, while cultivating a balance between the two. In practice, this can be difficult to achieve, so a continuous effort is required. Dedicate a leader who will be responsible for heading up the safety effort. It is also important to understand that fostering a culture of safety will always be a work in progress—the job will never be complete.

References

- ISMP 2018-2019 Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices for Hospitals. www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2017-12/TMSBP-for-Hospitalsv2.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2018.

- ISMP Medication Safety Self Assessment for High-Alert Medications. www.ismp.org/assessments/high-alert-medications. Accessed July 25, 2018.

- ISMP. Who We Work With. www.ismp.org/error-reporting/who-we-work. Accessed July 25, 2018.

Christina Michalek, BSc Pharm, RPh, FASHP, is a medication safety specialist at the Institute for Safe Medication Practices and oversees the operations of the Medication Safety Officers Society. She collaborates with health-system leaders and clinical staff participating in proactive risk assessments, targeted risk assessments, root cause analysis, and failure mode and effects analysis, in order to define and improve medication safety initiatives.

Sidebar

Opioid-Tolerant Patients

Opioid tolerance is defined by the following markers: Patients receiving, for 1 week or longer, at least: 60 mg oral morphine/day; 25 mcg transdermal fentaNYL/hour; 30 mg oral oxyCODONE/day; 8 mg oral HYDROmorphone/day; 25 mg oral oxyMORphone/day; 60 mg oral HYDROcodone/day; or an equianalgesic dose of another opioid, including heroin and/or non-prescribed opioids.1

Like what you've read? Please log in or create a free account to enjoy more of what www.pppmag.com has to offer.